How's your head?

text by Maé Biedermann, initially written in French, translated into English.

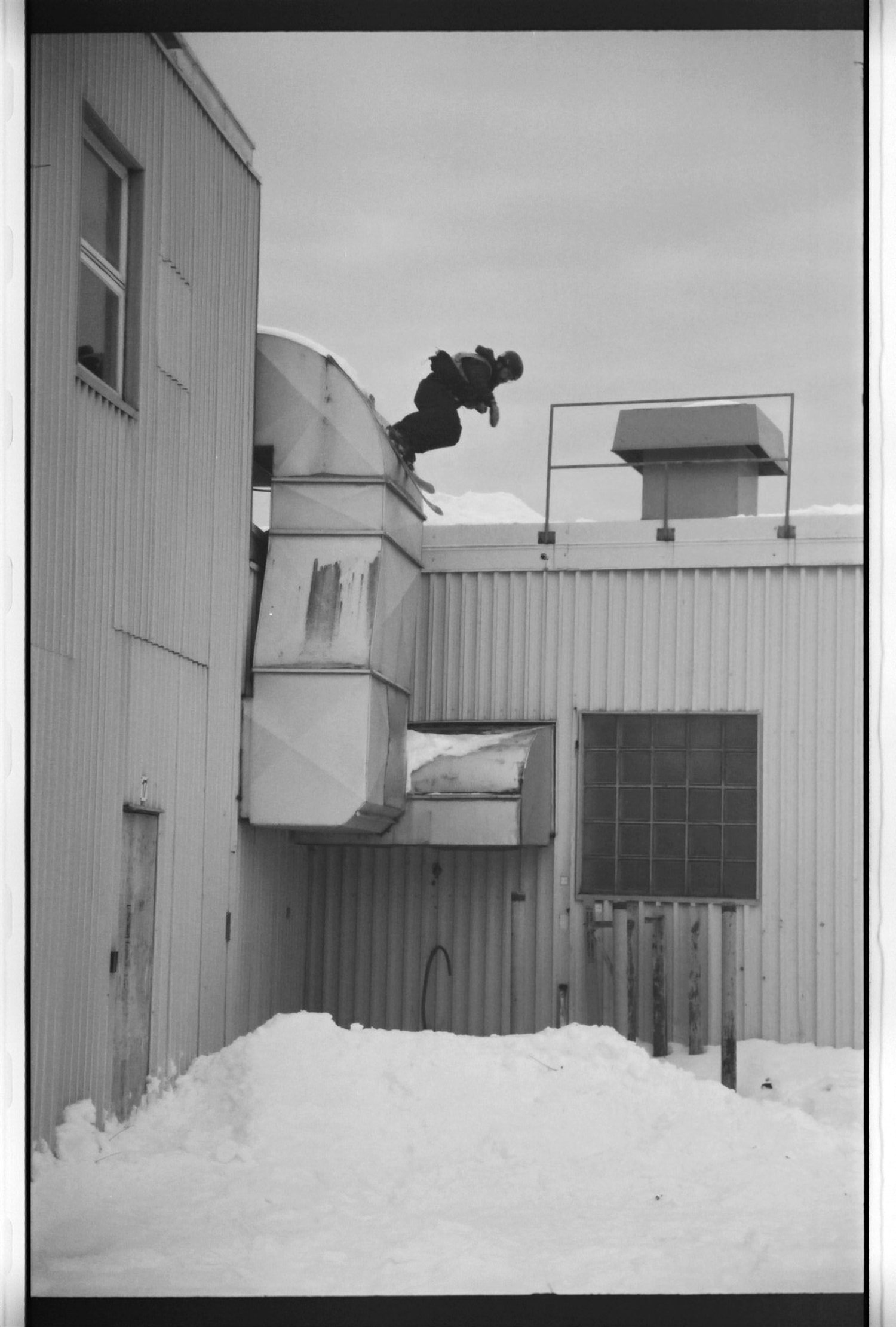

Skiing can be painful. Torn ligaments, dislocated shoulders and fractured tibias are all part of the sport. In freestyle sports more than in any other, concussions are commonplace. Despite growing awareness of the long-term consequences of repeated concussions - particularly in American football, where former athletes have developed early-onset dementia or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, with many deaths as a result - the subject of concussions is still taken lightly, especially in amateur sport. We laugh about taking the crash of the year. You wait a few days, then put your skis back on as if nothing had happened. But in some cases, recovering from a concussion can be far more complex.

"We classify the severity of concussions by observing the effects. There are two main categories. 80-90% are simple concussions, which recover in one to two weeks. 10 to 20% are concussions with prolonged effects," explains Boris Gojanovic, sports physician at Hôpital de la Tour in Meyrin. In his practice, he monitors sportsmen and women from a wide range of disciplines. The specialist reminds us that concussions, even if science is understanding them better and better, have not yet revealed all their secrets.

What we do know is that the list of symptoms is long. Headaches, sleep problems, loss of balance, lack of energy, sensitivity to noise and light, difficulty concentrating, memory loss, feeling foggy, etc. These symptoms are sometimes accompanied by mental health problems. "People may become anxious or depressed. The brain's equilibrium is disturbed, and neurotransmitters are not functioning properly," says Boris Gojanovic.

A mental battle

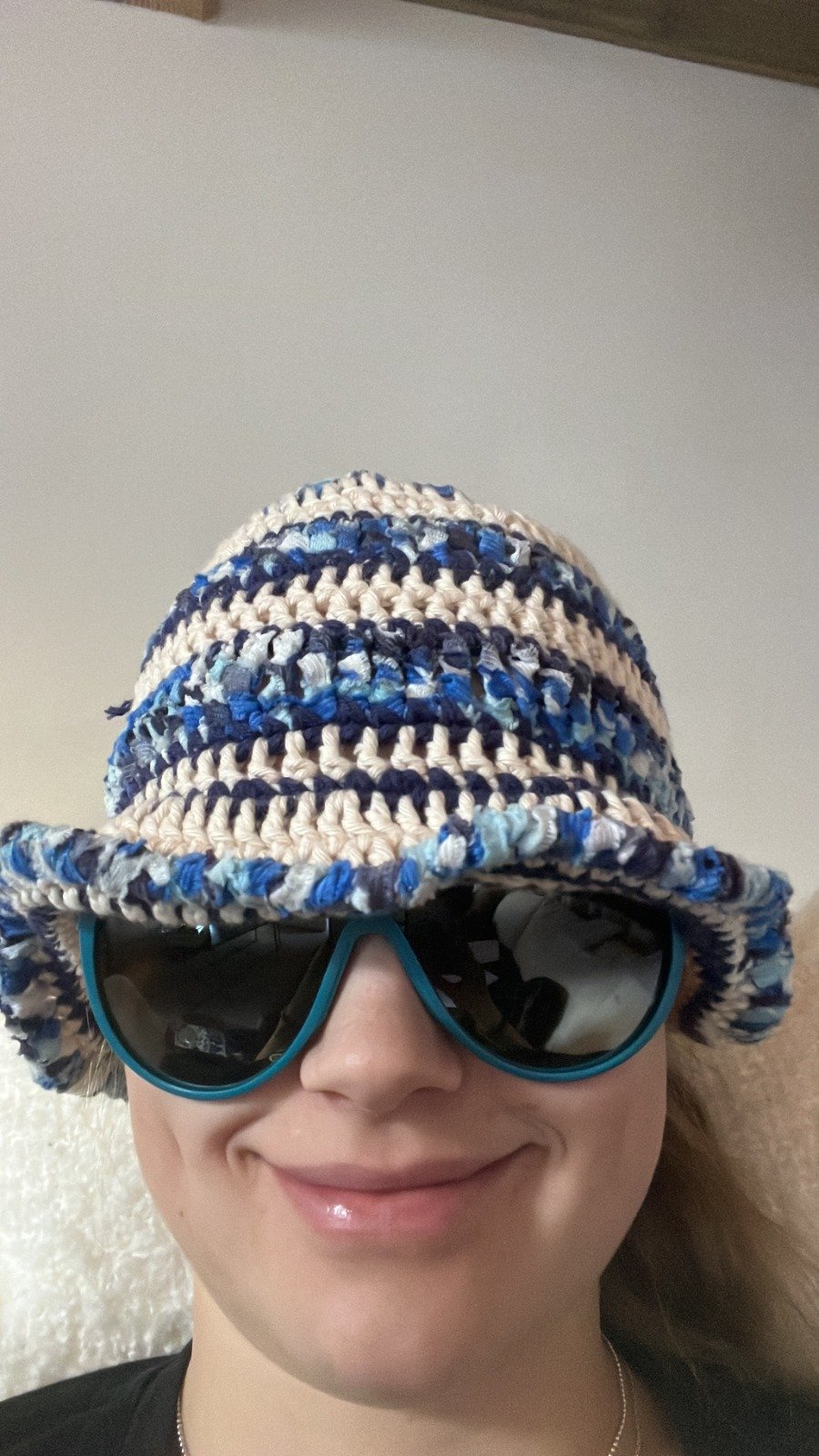

Emotions difficult to understand and manage, mood swings, irritability, but also depression and suicidal thoughts: some snowboard stars have dared to share their experiences, like Jess Kimura and Chris Grenier. And you don't have to be multi-concussed to suffer psychologically. Elsa Sjöstedt is a member of the Swiss Freeski B team. After each of her two concussions, in 2021 and 2023, she ticked off many of the symptoms listed above. She recovered in less than two months and was back on skis. "But honestly, the months that followed were horrible. I felt like I'd been cured, but mentally I wasn't doing well at all. I had so little confidence in myself, I was really afraid to do my tricks again," confides the young skier from Verbier. The pressure she's under from her teammates doesn't help. "In the first few training sessions, I got dizzy all over again. I'd stop skiing before the others. The guys on the team were criticizing and judging me. Since you can't see it from the outside. They thought I was faking it. It really hurt," Elsa laments. For many concussions, recovery from the most severe symptoms takes just a few weeks. But for Elsa, this stage is not synonymous with an immediate return to her former abilities. "When you feel 90-95% healed, the last percentage takes time. And that's just about the most important thing. During that period, I always felt like I had a mistake, a bug. It's horrible. It's not easy to get your confidence back when you know you really can't put your head together again in the next 3 months. Mentally, it's a battle," shares the skier.

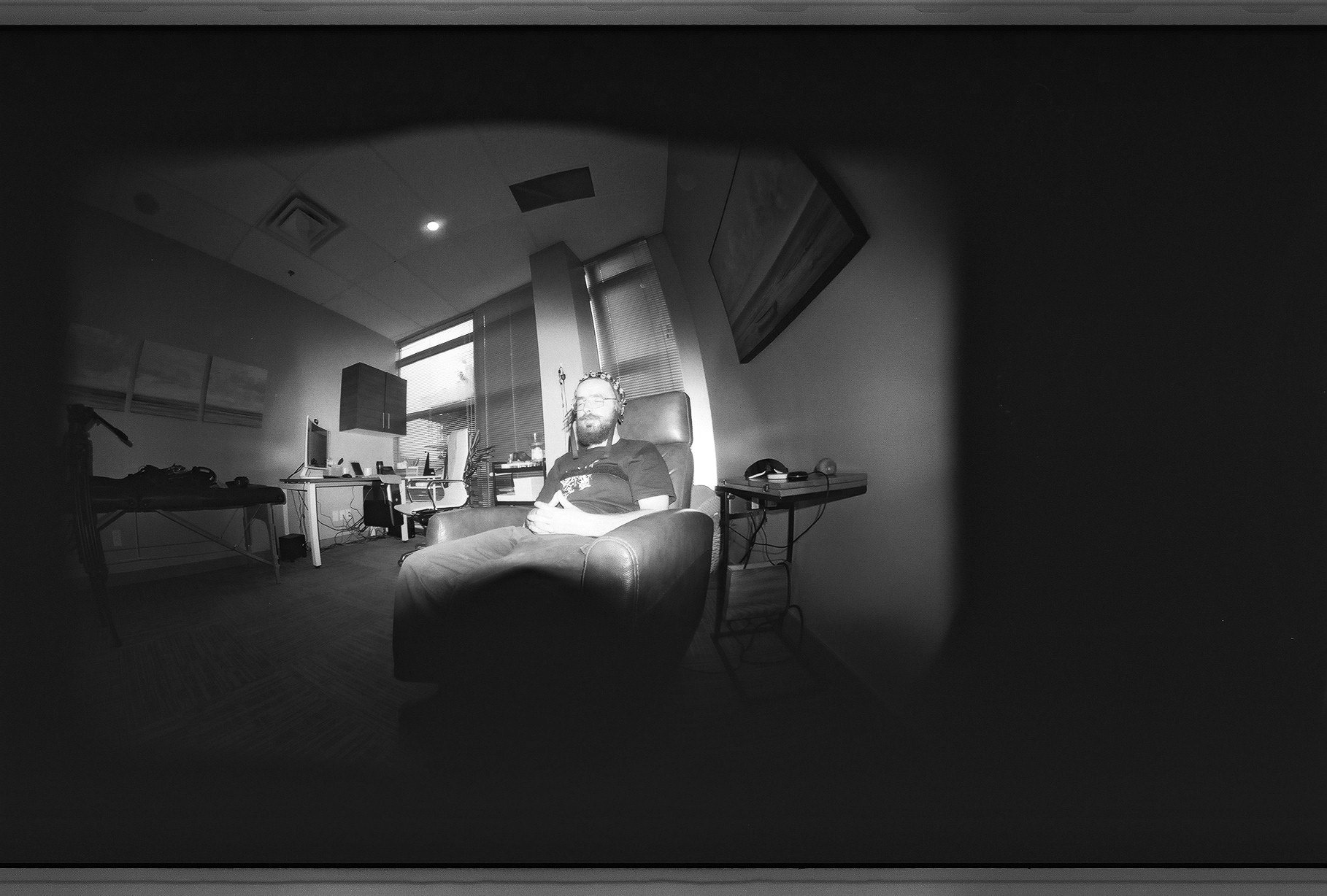

Quebec skier Rudy Lépine had to deal with psychological symptoms that plagued him for several years. "I'd had several shocks to the head and I had mental health problems in general. But I hadn't made the connection. I had problems with impulsivity, with managing my emotions. If something went wrong in my day, I'd go straight to bed and give up. I had major panic attacks. It was so intense that I didn't know what to do, I felt so bad," shares the Canadian rider. Rudy could still work and ski, but the state of his mental health was ruining his life. His girlfriend encouraged him to see a doctor. "I went for various tests. In the end, it was the psychotherapist who deduced that it was from concussion. The whole list of symptoms I had matched up," he says. He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to a head injury. Putting a word to his ailments enabled Rudy to begin psychotherapy and a treatment called Neurofeedback: a non-invasive treatment with an electrode headset, which helped him to overcome this trauma. "It's a bit like meditation mixed with mental exercises, to reconnect your neurons," Rudy explains.

A culture of silence

When symptoms persist after a month, this is known as post-concussion syndrome. "The problem is that athletes come to us very late, sometimes after several months. The problem is that athletes come to us very late, sometimes after several months, or even one or two years. And yet, we've been talking about concussions and their potentially dramatic consequences for 10 years now," worries Boris Gojanovic. Yes, it's worth remembering that after several concussions, the brain can suffer long-term after-effects, sometimes for life.

And a little taboo too? "Yes, quite clearly. Talking about your mental health is never easy. Whether to continue playing or skiing, athletes sometimes prefer not to say anything. In both cases, there's a real culture of silence," adds the doctor. But fortunately, things are changing in different sports. Federations have taken measures. In rugby, for example, as soon as a concussion is suspected, the player concerned is taken off the field and examined. Processes are put in place to assess athletes in the days and weeks following the shock. "In freestyle skiing, it's always a bit more freestyle," laughs Boris Gojanovic, who monitors the training frameworks of young French-speaking skiers. "Every sport has its own culture. Rugby players see themselves as warriors. With freestylers, you know you're going to fall flat on your face sooner or later. That's part of it," he says. And these cultures don't change at the snap of a finger.

Healing from concussion

Mathilde Gremaud, our multi-medalist from Fribourg, knows all about concussion. In 2021, she hit her head twice: first at the Chur big-air in October, then in Stubai in November. She's no stranger to concussions, but this time was different. "At the time, I thought I'd just fucked myself. I was afraid of losing my ability and having long-term problems, but I tried not to panic. The first week after the concussion, I was lost, a zombie..." says Mathilde. "Then I got better. I didn't have a headache anymore, but my eyes got tired really fast. In the car, it was exhausting to watch the road go by," continues the Gruyère native. Mathilde took advantage of the Swiss Freeski Team's departure for the Dew Tour in the US to treat herself to an express rehab in Denver. She headed for the Neuroplasticity Center, where she went a battery of tests of all kinds (balance, reflexes, vision, etc.). She then embarked on a week of intensive exercise with a lot of machines, each more complex than the last. "In the evening, after the training sessions, I was dead tired. The second I left the center, I shook my head like crazy to test it out! And I felt so much better! In less than a month, Mathilde was back on skis, but more importantly, she claims to have recovered from her symptoms.

Is there more damage if you have a series of concussions? Do we reach a critical point after a certain stage? "These are two assertions that practice verifies, but that science has difficulty verifying. Today, we have good research evidence that shows this, but no absolute proof," admits Boris Gojanovic. "If a concussion occurs shortly after another, which has not yet healed, we talk about second-impact syndrome. From what we see, this can increase the problem tenfold, even causing edema," he continues. There can be a certain cerebral fragility after two, three or four concussions. The brain can be more affected, even with weaker shocks. "It shows that there is a phenomenon of incomplete healing. I've already told athletes that they must stop their sport, but it often goes unheard..." notes the doctor. In his opinion, the key is to take the time to recover before resuming a high-risk activity. "The latest studies show that it's important not to put people on total rest for several weeks, in the dark, as sometimes happens. Ideally, rehabilitation should be carried out gradually and as quickly as possible", argues Boris Gojanovic.

Mathilde had the opportunity to obtain a rehabilitation as soon as possible after her injury. She was accompanied by health professionals and dared to talk about it to those around her. Virginie Faivre, a renowned halfpipe skier now retired from the circuit, has a different story. Dizziness, nausea, headaches, fatigue, sensitivity to light and noise... These symptoms accompanied the skier on and off for the last four years of her career. A final concussion would finally see her turn the page on halfpipe skiing at the end of 2016. "It was different 10 years ago. If I hit my head and stopped skiing for a few weeks, people would tell me I was making excuses!" confides Virginie. "It's an invisible injury and it's very difficult to talk about. When you make your crosses, it shows and people leave you alone for 6-9 months. People don't expect you to come back a week later. Concussions are pernicious. And I certainly didn't take all the right precautions," she regrets. The year she retired from sport, Virginie remembers falling asleep on the chairlift, her brain exhausted. Like Mathilde, she crossed the Atlantic to a neuroplasticity center in Florida. "I spent 10 days training there. I saw my daily progress and it felt really good. It was incredible to know that I could reeducate my head, just like with another injury. After a concussion, you can be proactive. You can't just wait for it to pass," explains Virginie.

Helmet or not ?

Then comes the fateful question: do helmets protect against concussions? "No, they protect against skull fractures, but not concussions," explains Boris Gojanovic. Does that mean wearing a helmet is useless for concussions? "You already know the answer: no, of course not! Even if it doesn't fully protect against concussion, a helmet does protect against fractures, more serious trauma and other damage such as hematomas." Concussion research has highlighted the importance of rotational shock, i.e. the pivoting of the head that leads to brain damage. Helmet companies such as MIPS and WaveCel have developed technologies that partially absorb this rotational shock. Although every fall and every head is different, a study by Portland's Legacy Biomechanics Laboratory shows that both technologies effectively reduce rotational forces. The reduction is between 29 and 66% with WaveCel, and between 11 and 66% with the MIPS model. So yes, helmets will prevent you from making a head injury worse, and can now potentially reduce the shock transmitted to your brain.

All our interviewees are convinced of the need to wear a helmet. Rudy has even invested in a field hockey helmet, specially designed for impacts on very hard surfaces. This makes sense for street sessions in Quebec City, where we sometimes crash headfirst into concrete staircases. But how do we get more helmets into the snowparks? The province of Quebec has opted for mandatory helmet use in snowparks. "I don't think it's the right solution," says Rudy, "A lot of people told me to wear a helmet when I was young. When I moved out west to Whistler, helmets weren't compulsory and I stopped wearing one," he continues. Rudy wears a helmet today. His doctor warned him that with the next intense concussion, the symptoms would return immediately, with potential lifelong sequelae. "Having found a helmet that fits and feels good, it's a big difference for me. I'm never going to tell someone they should wear a helmet. I prefer to tell my story, and maybe that will encourage others to wear one," says Rudy. Yes, many skiers are still reluctant to wear helmets in public, apparently for reasons of "style". But the younger people have models that display the helmet with class, the easier it will be to feel just as stylish with or without this protection, which is pretty essential after all.

Mouthguards are also an interesting way of reducing the impact transmitted to the brain. "It's been tested without any convincing results. But a study by Stanford University carried out tests with a team of American soccer players, and it seems that the mouthguard can absorb part of the shock, even without the blow coming from the jaw", reports Boris Gojanovic. "It's also worth remembering that strengthening the cervical muscles helps to better absorb forces, particularly rotational forces", adds the doctor.

However, formidable training and innovative protection will never completely prevent concussions. So let's prevent where we can. When professional skiers admit that they didn't really think about concussion until they were suffering its consequences, it's clear that amateurs are still sorely lacking in information on the subject. The risk is that some people go through this difficult stage without knowing what's happening to them, without daring to talk about it, and without being able to treat the symptoms. Mathilde was able to treat them as quickly as possible. Elsa went to the Swiss Concussion Center in Zurich after her first concussion. Rudy was followed by a psychotherapist and treated with Neurofeedback. The key is to intervene as soon as possible and get help. In freestyle skiing, it's impossible to prevent reckless post-adolescents from landing on their skulls. But it is possible to give them all the keys they need to avoid the long-term consequences of a concussion. So what do we tell young people who take part in high-risk activities? "You have to start with the basics: sport, yes, but only in good health. There's too much pressure on young people to perform. We need to empower them and give them the chance to say if something happens to them. It has to come through education, in sport and at school," pleads Boris Gojanovic. And in magazines, let’s add.